BEEF : One Year at the Brunswick Club : A Reflection on Events by Vicky Smith, April 2018

While the artistic events taking place at the Brunswick Club since the artist collectives BEEF, CHAMP and Residence began occupying it in 2017 are diverse, they are unified by a frequent response to the material conditions of the building itself. In this regard they might be understood by comparison with similar instances in which artists inhabited and responded to formerly disused public spaces in attempts to critically re-read their purpose and history. Although many examples of creative re-imagining of former public buildings for studio and exhibition space might be given, I refer primarily to the exhibition Rooms at P.S.1 in 1976 in Long Island City. This group show intervened in the architecture of a former public school and Rosalind Krauss’s reading of it through the sign of the index attracts my particular attention because of the indexical character in artworks by BEEF members (at the Brunswick Club). In this discussion, I’ll reflect upon how the fabric and material history of the building itself impacted this aesthetic of indexicality, and how such art occurring today in Bristol breaks with and/or develops the indexical practices of Rooms. To support an understanding of the enquiry into the relationship between work and relaxation in events at the Brunswick Club, I will also briefly refer to critical theorists such as Theodor Adorno and Walter Benjamin for their astute analysis of the conditions of labour, industry and leisure during the modernist period.

THE INDEXICAL

An indexical sign is one whose resemblance to its referent is along the axis of the physical. It is not a representation so much as a mark or imprint that occurs as a result of material contact between the object and its trace. Examples given [1] are those of the appearance of smoke alerting us to fire, and the spinning of the weathervane as an index of wind. Whatever the manifestation, that which is indexed, or pointed to, is the cause, or source.

The indexical sign is of interest to modernist artists and art historians because, neither pictorial nor abstract, it instantiates a break with illusionistic verisimilitude. Krauss’s essay Notes on the Index: Seventies Art in America focuses on the P.S.1 exhibition as one that typified the impact that the technology of photography has had on abstract art. The artists involved, such as Gordon Matta Clark, (whose major works consisted of architectural interventions such as slicing an entire house in half as a form of social comment) adopted mainly the discipline of installation. They worked with the derelict state of the building itself as medium, taking aspects of its fabric, and through actions of removing, cutting into, inverting, rubbing and transferring parts of the architecture and its decor, pointed to the building itself as the message of the artwork. During this period the consensus was that photography possessed a documentary quality owing to its status as a direct trace of the real. Using these methods of selecting, cropping and directly pointing to the building and its decor, the un-coded character of photography was translated to that of installation art.

THE AURA OF THE BRUNSWICK CLUB

The exhibition at P.S.1 and Krauss’s reading of it is worth remarking on for its correspondences, to varying degrees, with the events and exhibitions occurring at the Brunswick Club. In both cases disused urban real estate on the fringes of the city have, or are being, leased by, or for, artists’ as studio and exhibition space. As with the P.S.1. group approach to indexing the fabric of the building, with its strong coding as a formerly public institution, the Brunswick Club’s history of public use has also been directly and indirectly referenced by the current Bristol inhabitants.

Several BEEF artworks, in responding to the history and material of the building itself, adopt indexical methods. This tendency can be understood in that the existing practices of individual artists within the collective had long sustained enquiry into site and material history. My own practice has gravitated increasingly toward exploration of traces, stains, soiling and marking and has been further influenced by the collective orientation toward indexical art and also by the aura of the building.

The concept of the aura was developed by Benjamin in relation to the status of the image in the age of mechanical reproduction: however close to hand an object or image may actually be, it has an appearance of distance (Benjamin, 1969). The aura manifests as a consequence of a material relationship and prolonged physical contact between a person, or people, and objects or places – a timespan during which the subject is transmitted into the object. Working along similar principles as the indexical, the aura is not a sign but a phenomenon, and some go so far as to suggest that it is an actual medium that envelops and connects things (Hansen 2008: 351) an example being that of a coat that has acquired the mold of its wearer (Hansen: 340).

THE ENTRANCE HALL/LOBBY

I briefly refer to work by members from the other (than BEEF) collectives because it so readily exemplifies indexical art. Yet my main focus will be on the projection and the amplification of analogue sound and the moving image and the different quality of indexicality generated therein.

An aura exuded from the now remote yet not so very distant past of this habitat for working and socializing males. It manifested as trace in the traditional décor across the segregated male/female spaces, the focus on competition, evident in the discarded trophies and snooker cues and in the insistence on obedience, with type-faced regulations throughout, such that, despite the buildings designation as an environment for leisure, an individual might never fully relax.

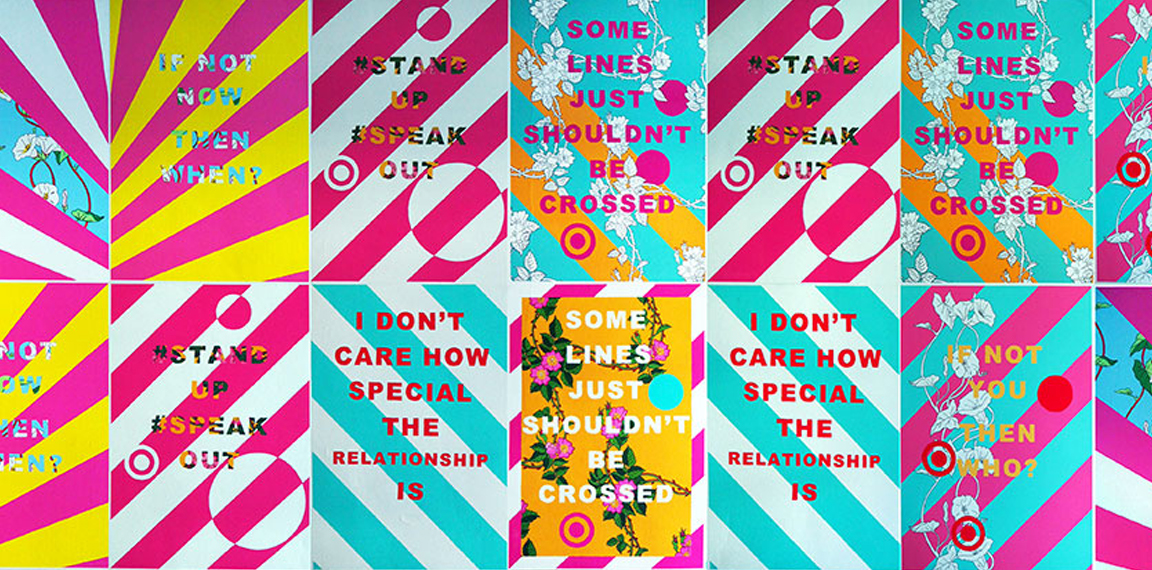

Signs that strongly demarcated gendered zones, such as the male/female coded figures on doors, were switched over to neutralize the toilets. The prohibitive typo-graphics were translated by studio holder Dawn Giles into a set of posters lining the lobby, that mimicked in their design the gender coded striped wallpaper or floral of the ladies spaces. Reminiscent of Jenny Holzer’s truisms and inflammatory essays demanding change in the political order (1977 -79) the Brunswick rules were replaced with agitations by women, emblazoned with statements such as ‘stand up, speak out’. With this strategy of ‘camouflage’ (Giles), a variation on the indexical is proposed.

CHAMP’s Lizi Hoar found a photo onsite depicting a name handwritten on a tag and a packetof marrow seeds: she took this to refer to the winner of the Brunswick club’s horticultural society competition. Concerned to celebrate the achievements of the grower, Hoar elevated the forgotten relic to the status of art object by gilt framing and enlarging it to A1 size. By simply blowing up the original image to a much bigger size, male clichés of exaggeration and inflation are invoked.

Fig 1. Dawn Giles: Dazzleships

Fig 2. & 3. Lizi Hoar: Marrowman

THE SKITTLE ALLEY

The different BEEF art works that variously registered the dated décor and faded ideologies of the Brunswick Club directly and indirectly index its rich history, and the club’s games hall inspired a number of events. Geared toward amusement, the gag, the ludic and the vaudevillian, the Fluxus art movement exerted a strong influence on these artworks.

The particular design of the skittle alley and its dramatic function are explored in David Hopkinson’s Front First or All- In? [2] installed during the Members Show (8-10th Dec 2017). At one end of the alley a projector and camera positioned closely behind a skittle ball strongly backlight it, with the effect that an enlarged hemispherical shadow is thrown onto the wall at the opposite end. This paracinematic piece is reminiscent of Anthony McCall’s Line Describing a Cone (1997) or Tony Hill’s shadow-play pieces. In its simple translation of light and geometry into line, perspective, scale and chiaroscuro it is strongly formalist, whilst the low-key lighting amplifies the theatrics of aim, stasis and kinetics and also indexes the materials and the principles of the game.

Figs 5. & 6. Front First or All- In?: David Hopkinson

Fig 7. Bicycle Tyre Track: Vicky Smith

For the event Physicality and the Moving Image (27/10/2017) [3] I adapted my own film/performance Bicycle Tyre Track to the narrow course of the skittle alley to bowl my bicycle down the straight track and to print its tread along a strip of 16mm film. The projectable filmic image is the impression of the substance of both the tyre and the alley, indexical in the sense that the mark points to the thing that caused it. As both the sound and picture areas of the film were rubbed with these traces, upon projection the noise of the contact between the grooved tread of the rubber tyre and the fine grain of the wooden casing was reiterated as an audible rhythmic rumble.

Now, this dimension of the indexical dimension of sound demands further attention. Unlike say, an encounter with footprints in the snow pointing to a past event of someone having recently walked by, an indexical sound exists in the present space – unless that is it exists as a recording of the sound. This layering of the playback of a pre-recorded sound from the past alongside the same live sound in the present was explored in Melanie Clifford’s Melanie and Her 5 Fans. This piece can be related to the conceptual art tradition that sought to give materiality to invisible volumes, such as Michael Asher’s Airworks (1969), in which fans were installed to sculpt air and to demarcate audience space.

Fig 8. Melanie and Her 5 Fans: Melanie Clifford

Probably due to the lack of ventilation in its basement location, the skittle room is equipped with overhead fans. These mechanical instruments were exploited for their audible qualities in Clifford’s performance/install in the event Experimental & Expanded Turntabling (06/01/2018). On an earlier occasion Clifford recorded the differential acoustic frequencies that were generated by the rotating blades of the fans as they were run through their various settings. Later, as a live performance in the same skittle room, Clifford then played back the recordings of these sounds, manually rotating the dub-plates on the turntable whilst adjusting the fans to run once more at fluctuating speeds. The vibration generated from the recorded sound of the fan wings then altered the acoustic pressure in the room, which in turn subtly modified the rotation of the fans in real time and so on, in a feedback loop. In this way Clifford conceives the fixtures, the ceiling and the architecture itself as more than mere spectators (fans) and rather as active participants in the artwork. This piece actually effects a reversal of the relationship of causality given in the example of the weathervane, which, blown about by the breeze, indexes the presence of wind. In this case, it is the increased presence of air currents that are the sign and they index the referent of the fan as the instrument that caused it.

As with Hopkinson’s consideration of the formal aspects of the club’s games room, and my own Bicycle Tyre Track in which correspondences between reel and wheel, the length of the 16mm filmstrip and the long alley course were considerations in the work, formal analogies between the rotational movement of both turntables and fans also informed Clifford’s piece. Beyond a doubling at the level of form her process also frequently involves the reiteration of an image or sound by filtering the representation of a thing through the actual substance of whatever material is being used. For example, in the event The Brunswick Light Ray Process (I will discuss this shortly) in a constant to and fro between image and referent, the projected imagery of windows and window frames was refracted through other glass and transparent materials: objects, such as multiply stacked up glass ashtrays and beer glasses containing amber sediments, common to the ballroom bar.

THE BALLROOM

The Brunswick Light Ray Process was held at the Brunswick Club on (23/11/2017). The process was inspired by found historical documentation pertaining to a company called Brunswick records who, in the 1920s, developed an electrical method of recording sound, and the serendipity of our shared ‘Brunswick’ name, with BEEF as specialists in analogue. The light ray method was then brought together with analogue projector technology by analogue tinkerer Matt Davies who translated the process into optical sound. Optical sound is a technical particularity of the analogue film system whereby sound exists on the same piece of film as the image and equally is read by light. Known as optical because it is ‘seen’ by the projector’s photoelectrical cell, which converts light into electricity and then sets up a vibration that is audible, many experimental film-makers, including Lis Rhodes Dresden Dynamo (1971), have exploited the synaesthetic possibilities of this analogue specificity. Davies customized this process to make an optical microphone, routed outside the machine to amplify sounds in the environment external to the projector. All the happenings as described below were filtered through this amplification mechanism.

Clustered together on the dance floor the performers and their machinery, cables, objects and decks enacted ‘the process’. A series of acts erupted, seemingly spontaneously, and without hierarchy in a manner strongly relatable to the inter-media Happenings of the 1960s/70s. This line up of variety and novelty also invoked the vaudevillian popular entertainment more properly belonging to the club’s ballroom tradition.

Two weeks previously BEEF’s Shirley Pegna held a workshop Sonic Hide and Seek (04/11/2017) in which participants were invited to translate and re-work the clubs less obvious acoustic specificities. This attenuated listening to the site appeared to motivate aspects of the Brunswick Process. Fixtures of the ballroom, such as the overhead neon strip lights, were choreographed to flick on and off in quick succession. Electricity was taken as medium and as music: light arcing through the tubes caused the glass to sing and most tangibly exemplified the concept and process of converting light into sound.

Fig 9. Tap/Sew at The Brunswick Light Ray Process

Of all the acts to emerge from the process I want to focus on the duet Tap/Sew as its hybrid entertainment/ industry/ high art status exemplifies the club’s evolution into an artists exhibition space and it encapsulates certain themes of my discussion. Tap/Sew brought together the escapism of showbiz with the repetitive labour of industry as Eliza Lomas tapped the ballroom floor to the hum and pace of a sewing machine manually operated by Sam Francis. The sewing machine has been brought into the projection event previously in Annabel Nicolson’s Reel Time (1973), a task based film/performance that drew analogies between projector and sewing machine technologies, the fragility of materials and physical vulnerability.

Lomas danced, often to the brink of exhaustion, thereby suggesting an inseparable bond between labour, relaxation, work and leisure. In a capitalist economy, even downtime is regulated: this and the alienating effect of technology was much debated by critical theorists during the 1930s and reference to this theory nuances a reading of Tap/Sew. Adorno considered all technology, the leisure space of cinema included, to be yet another capitalist tool through which to exploit the worker. ‘The machinery is more often than not victorious and ever more insinuated into our lives, especially at those moments when we think ourselves most relaxed, most at leisure’ (Leslie, 2010). Adorno recognized the possibilities that might be derived through technical failure as a means to interrupt the capitalist fabric. Esther Leslie, reviewing an exhibition of animation, reads this in relation to the intentional breakdown of regular language as it is made visible in experimental film.

Both Adorno and Benjamin observed that a sense of release from subordination could be reached by laughing at the conditions of bondage. As Leslie develops, Benjamin proposed that positive experience from the alienated conditions of labour could be experienced through the mimicry of technology. Such mimicry is re-enacted in Tap/Sew and this piece produces both a pleasurable experience through the viewing of fine dancing and specialist clothing and through hearing the taptap/clackclack rhythms. It also elicits a slightly distressing response as the work touches on real issues of endurance, breakdown and the loss of self-composure as it leaks into the space of artifice, performance and entertainment. One sharp distinction between Tap/Sew and Reel Time is that the latter, though subversive, cannot easily be read as playful. Nicolson proposes the real consequences of mental and emotional exhaustion, not through physical breakdown or through the malfunctioning of the machinery, but through the laceration of the sewn object of the filmstrip, ‘stitched’ beyond repair.

****

A question framing my discussion of the indexical character of art events held at the Brunswick Club during 2017/18 is how, and if, this work builds on the type of projects taking place at P.S.1 in 1976. Methods that characterised the P.S.1 project, such as cutting into wood, or taking rubbings of surfaces, are actions primarily allied to sculpture, printmaking and painting. It is this reference to traditional artistic mediums, yet in the form of installation and through the logic of the trace, that Krauss finds remarkable. BEEF however, is a collective of film-makers and sound artists and we work predominantly with analogue media.

The onset of the obsolescence of analogue film at the start of this millennium ushered in much debate regarding the indexical status of cinema. [4] Mary Ann Doane proposes that our investment in the photographic is less about its capacity to capture the resemblance of things and more to do with a knowledge that these things, now sealed in the photographic surface, actually once existed (Doane 2007: 147). With analogue film and photography the light that strokes the sensitive photo emulsion is connected to and the same as that which enveloped the object, while digital media loses the connection between the image and its referent and is no longer accepted as verification of existence.

In much of the sound and film installation expanded works at BEEF the manifestation of index as trace persists. The social history and work-leisure aura of the building is indexed variously through different forms, methods, objects and processes, such as direct-on-film, audio vibration, installation, performance and kinetics. Ultimately however, these works are less concerned with an enquiry into notions of the analogue /photograph as the bearer of truth so much as employing the unadorned un-coded character of the index as a means to give transparency to process: one that is important to the field of experimental film and that lies at the heart of expanded cinema.

In this essay I’ve merely touched on the wealth of events that have taken place during one year at the Brunswick Club and I look forward to the developments during the forthcoming year.

References

Benjamin, W. (1969). Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Berlin: Schocken Books.

Doane, M.A. (2007). ‘Indexicality: Trace and Sign’, differences: Journal of FeministCultural Studies 18(1), pp. 1-6.

Doane, M.A. (2007). ‘The Indexical and the Concept of Medium Specificity’,differences: Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies 18(1), pp. 128-152.

Hansen, M. (2000). ‘Benjamin’s Aura’, Critical Inquiry 34(2), pp. 336 -375.

Leslie,E (2010) ‘Shudder’: Animation at the Drawing RoominLondon: London: Animate Projects.

[1] In semiotic studies Charles Peirce during the late 1800s distinguished between the signs of index, icon and symbol. See ‘Philosophical Writings of Peirce’. [2] The artist states that the title of his install references methods of West Country skittle playing traditions [3] This symposium and exhibition event was organized by BEEF member Rod Maclachlan in conjunction with UWE Bristol. [4] See for example October Journal (2002) no. 100: Spring 2002; Millenium Film Journal (2011) ‘Material Practice from Sprockets to Binaries’ Vol. 56; Knowles.K (2017) ‘(Re) visioning Celluloid: Aesthetics of Contact in Materialist Film’ in eds. Beugnet, M.Cameron.A, Fetviet, A. Indefinite Visions: Cinema and Attractions of Uncertainty London:Barnes and Noble.